ABSTRACT

The use of most unclear discussion (MUD) cards enable anonymous questioning free of judgment, to foster student engagement. These cards offer professors insightful feedback on class progression, aiding in adaptive teaching approaches that balance meeting student needs and maintaining appropriate challenge levels. Particularly impactful in cumulative courses, this methodology amplifies student involvement in class preparation, demonstrating its efficacy in enhancing education approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Most unclear discussion (MUD) cards are a tool used within the active learning paradigm and learner-centered approach. They serve as a continuum approach, connecting lecture and workshop sessions. These cards provide students with an opportunity for close feedback, allowing them to reflect on and assess the topics they find unclear. The anonymous nature of MUD cards also encourages students to ask questions without fear of judgment, even about topics they might consider inappropriate or obvious.

The MUD cards are a variation of the One-Minute Paper technique, specifically focused on class content and filling knowledge gaps. This technique is a teaching and learning tool that is particularly suited for introductory courses across diverse academic fields: students can freely pose queries directly linked to class topics and explore related subjects that may eventually prove relevant to their degrees. This approach facilitates early-class discussions around students’ queries, inspiring a sense of cross-disciplinary relevance into the classroom, especially for those yet to feel at ease asking questions in a new learning environment.

This publication outlines experiments done in some programming courses for BSc students.

Origins of Feedback Tool

Adhering to the active learning paradigm, which prioritizes a learner-centered approach to education, students are actively engaged in their learning process throughout the semester. Within this context, most unclear discussion (MUD) cards serve as a continuous bridge between lecture and workshop sessions, seamlessly connecting one session to the next.

MUD cards serve as a valuable end-of-class feedback tool, empowering students to introspect and identify the topics they find most perplexing and in need of clarification. Notably, these cards maintain anonymity, providing a safe space for students to raise questions they might hesitate to ask in a classroom setting due to concerns about appropriateness, simplicity, or perceived obviousness. Free from judgment, students can candidly express their uncertainties.

This pedagogical approach is not entirely novel, tracing its origins to the work of Mosteller, a statistics professor at Harvard University [1]. Mosteller’s initial publication outlined three questions posed to students in the final minutes of each class: “What was the most crucial point in the lecture?”, “What was the muddiest point?”, and “What would you like to hear more about?”

MUD cards can be viewed as a tailored variation of the One-Minute Paper technique [2], specifically tailored to address gaps in student comprehension within the course content. In contrast to eliciting specific responses such as “What are the two most significant things you’ve learned during the session?” or “What questions are still on your mind?”, MUD cards provide students with a blank canvas to express which aspects of the session they perceive as the most unclear, promoting a deeper understanding of course material.

More recently, in 2015, Keeler et al. [3] also studied the possibility of questioning class students on what topic was the most surprising, in order to develop the metacognitive skills that are a characteristic of expertise. In the following years MUD cards continue to be used for instructors to get across some blind spots during their courses, as reported by Krause et al. [4] in 2020, which state that uncovering and addressing such issues makes teaching both more challenging and rewarding with the opportunity of improving the classroom experience for both students and instructors.

Structure of our MUD Cards

Cards are made from A6-size paper sheets in which a large area is clear for students to fill in their answers with by text, a drawing, or other means.

During the reported experiments, the MUD card was changed to have an exclusive feedback area, as some students were finding it easy to skip their duty by simply writing a positive and vague feedback comment such as “good lesson”.

At the top of the card students can read “Which was the least understood topic during the class? Is there any topic you want us to review? Is there anything you want to know more about, from the class or related to programming? Is there anything from the class before you feel you did not get it?”.

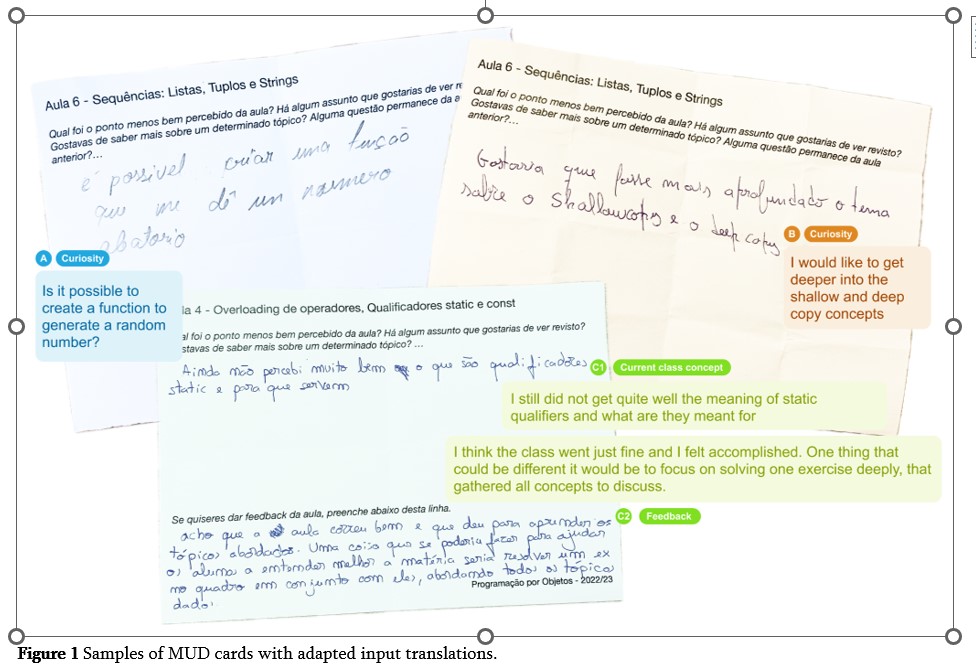

Figure 1 displays three MUD card examples. Exhibits A and B represent two upcoming topics related to the current class, as seen in the initial version of the MUD cards. Meanwhile, exhibit C showcases the last revised version incorporating a covered topic alongside a feedback comment. As the inputs are originally in Portuguese, adapted translations were included in the figure to enhance its comprehensibility.

Benefits for Both Student and Instructor

The cards get across with students and teachers in a different way, but the main consequence is to allow students to take some control over which topics are covered in the beginning of the next session, and teachers to better understand how are students understanding the class’ concepts and practices.

From the student’s perspective:

– Towards the end of the class, students can anonymously submit new MUD cards with their questions, delivered folded on the teacher’s desk, on exit.

– In the next class (or before the next session, if a student requests), students will receive answers to all the questions, indiscriminately, by the teacher, right before starting the next class contents.

From the teacher’s perspective:

– Carefully read and categorize the received MUD cards based on different criteria, such as topic (current class concept, class before concept, next class concept, beyond the course curiosity, feedback, …), subtopic (which is the concept in question, regarding the topic), level of detail (if the question is low, medium or highly detailed), and format (by text, diagram, …).

– Determine the best approach to address the questions, which may include delivering presentations, lectures, or creating FAQs tailored to the students’ needs.

This execution, although with some initial learning curve, should last between 1 to 0.5 hour time commitment per advancing topic. The number of students will have a direct impact on the number of questions to address, but the teacher can always categorize and group them into clearer questions for better answers.

Results and Summary

The MUD card tool has proven to be highly beneficial in assessing students’ understanding and pace throughout the semester. This method allows students to prospect a more personalized source of in-class discussion competing with generative artificial intelligence models such as ChatGPT whose students wrongly feel to be correct and effective sources of information.

By analyzing the number and nature of questions related to late and future concepts, and the detail in descriptions, teachers can gauge student progress.

The cost for teachers is relatively low, as preparation can be integrated into the usual routine, with additional time required to present answers to students.

Student feedback on the MUD card practice has been overwhelmingly positive, after inquiries made to students on this technique. Across four semesters, we surveyed 114 students to gauge its impact on their studies, the teacher performance, and the effectiveness of MUD cards. Using a scale from 0 to 9 to rate its usefulness, where 0 meant that “this method is wrong or never brought a useful answer”, and 9 that “students always saw their questions successfully answered”, 40 students responded, yielding an average score of 8.4, reflecting its success.

Moreover, we provided students with an opportunity to share their thoughts openly, and their responses showcased a solid understanding of how this method contributes to their learning objectives. To mention a few: “I think it’s an innovative way of dealing with students’ doubts so that they don’t feel embarrassed.”, “The work was very good, I especially liked the mud cards strategy and starting classes by answering the questions asked.”

A ready-to-use toolset for a broader community to try on MUD cards is available in http://teh23.ruilop.es.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to professors António Neves, João Rodrigues, and Daniel Corujo for having opened the opportunity for this work during teaching assistance in their courses, and to Pedro Teixeira for the uncountable hours of discussion on learning approaches, methodologies, and tools.

References

[1] F. Mosteller, “The ’Muddiest Point in Lecture’ as a Feedback Device,” On Teaching and Learning: The Journal of the Harvard-Danforth Center, Vol. 3, pp. 10-21. 1989.

[2] T. A. Angelo & K. P. Cross, “One-Minute Paper Technique”, Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers, 2nd ed., Jossey-Bass. Publishers, pp. 148-153, 1993.

[3] Jessie Keeler, Bill Jay Brooks, Debra May Friedrichsen, Jeffrey A, Nason, & Milo Koretsky, “What’s Muddy vs. What’s Surprising? Comparing Student Reflections about Class,” Proceedings of the 2015 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Seattle, Washington, 2015, 10.18260/p.25067. Available: https://peer.asee.org

[4] Stephen J. Krause & Sarah Hoyt, “Enhancing Instruction by Uncovering Instructor Blind Spots from Muddiest Point Reflections in Introductory Materials Classes,” Proceedings of the 2020 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access, Virtual Online, 2020, 10.18260/1-2—34570. Available: https://peer.asee.org